I keep reading doomsday declarations about what AI art will do to actual artists and their possibility of getting paid and at this point I’m convinced that everyone writing about this is missing the point. Artists have not been paid what they’re worth for a long time, either by exploitation or outright theft of their work. The homogenized, regurgitated slopification of art — no, I’m sorry,

content — has been going on forever in the form of Save The Cat making all Hollywood movies the same, the MCU taking over cinema, the Penguin Random House/Simon and Schuster merger (including a hearing where they admitted they have no idea how books get popular), the insane scheduling requirements on Instagram to get any attention whatsoever, “crunch time” ruining game creators lives, all the way down to T-shirt bots trawling Twitter. If you read Little Women, Jo gets paid about the same amount in dollars for her short story during the

Civil freaking War as a writer today would get upon winning a similar contest. I’m not saying it can’t get worse, but the idea that AI will change the fact that companies and unscrupulous individuals will do anything to avoid paying artists for their work, up to and including outright theft, by convincing them and everyone else that all “art” is essentially interchangeable, is nothing new, to the point that I wonder where the fuck anyone making these statements about AI art has been for the last ten years at least.

Art or “Art” is not the point here. The term "AI art generators" obfuscates what these programs are actually doing, and that's laundering intellectual property.

For AI to do anything it needs to be trained on a large data set. So, for an AI to make “art”, it needs to be trained with a large data set of “art”, which through “learning” it can then remix trends into the images it spits out. So, the biggest, most obvious question, then, is where is this “art” it is being trained on coming from? By the image sets DALL-E generates online, it's very obvious that the art it has used in its sample is not free, based on the fact that what it is best at creating is obviously someone else's intellectual property. It can generate very reliably images including "Pikachu" or "in the style of Frank Miller", meaning that the program must have analyzed tons of images of Pikachu and by Frank Miller, and not one article I've seen talking about art generators actually notes that to use these images, the user would have to actually pay whoever owned these images and properties to use them commercially, even if the final piece being used was generated by one of these AI programs.

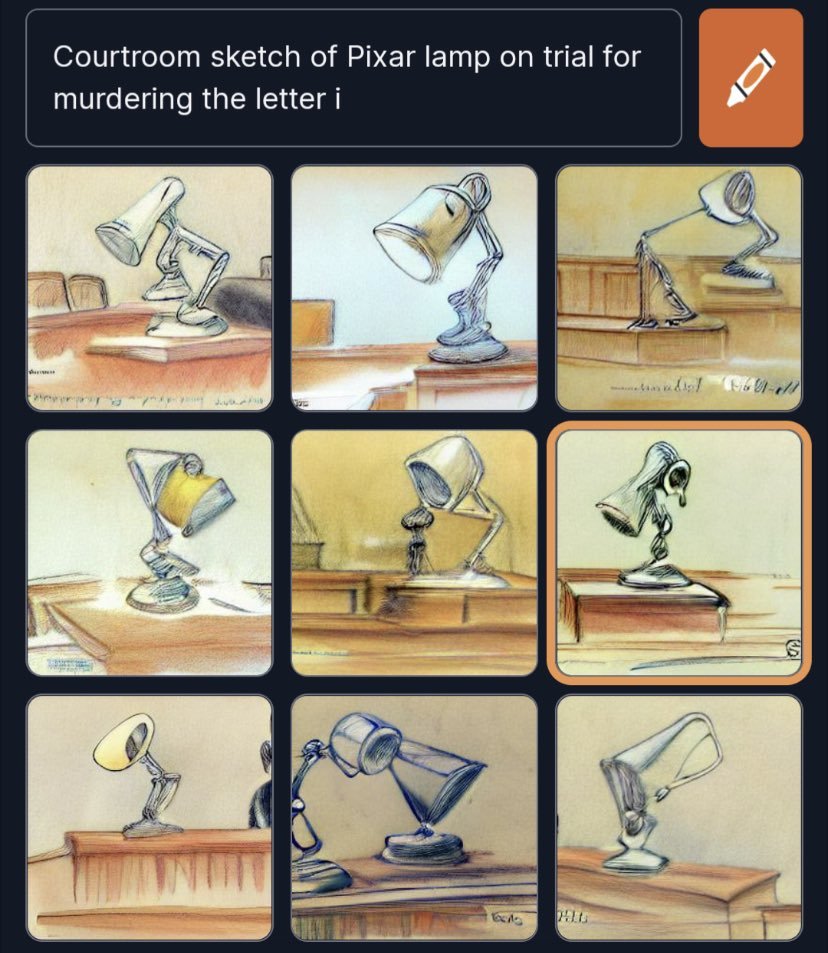

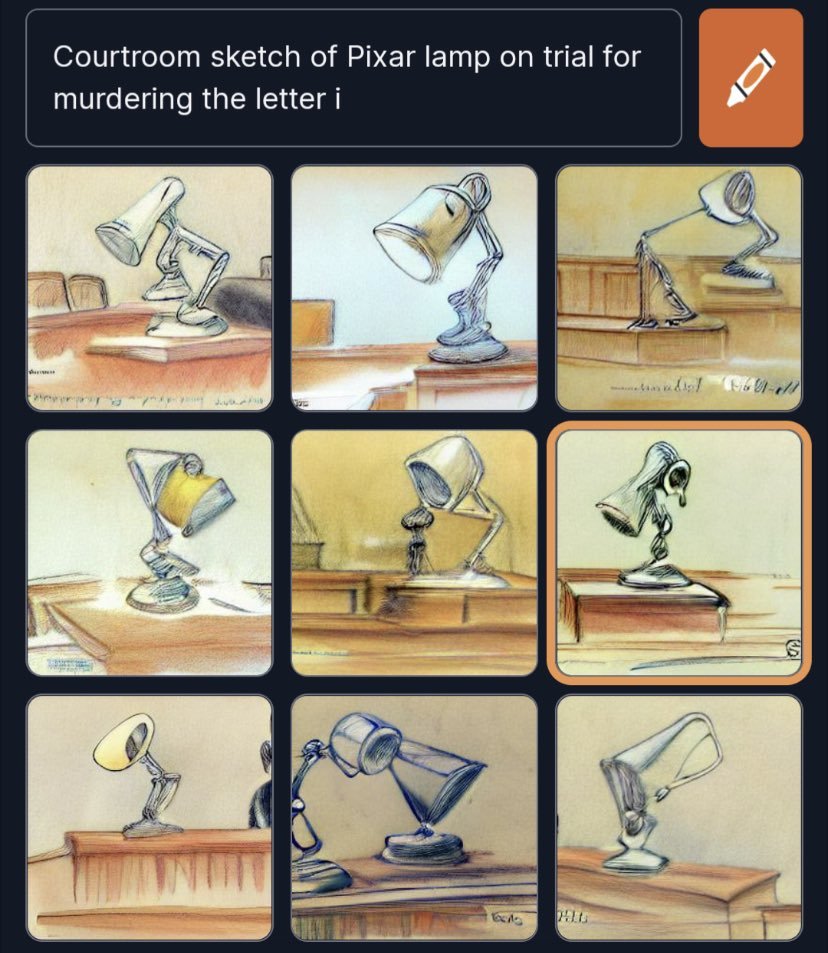

DALL-E is able to exist and pull from these images probably because it's assuming that the use of copyrighted images and properties would be protected under fair use, with the argument that it's not for commercial use and the demonstration with these commercial properties is a part of the educational or scientific value of the generated pieces. However, I could imagine a large company like Disney deciding that it did not like users creating images of Mickey Mouse at strip clubs and send a cease and desist request that all Disney properties be taken out of the learning set, which would leave users suddenly unable to make images of Darth Vader making the first pitch in Dodger Stadium or courtroom sketches of Sora being tried for manslaughter.

But Disney is Disney. What about everyone else? I am not a lawyer, but I think this gets both easier and harder. As long as we're discussing fair use of images, Mickey Mouse at a strip club could be argued to be a parody or criticism somehow, while, say, if a drawing I made of a flower I found in my backyard was added to the data set, it would be really hard to argue anything made with it would be parody or criticism of the original work because I'm a nobody. There would be nothing specific in that image to parody or criticize because I am not known enough to parody or criticize. The use of my artwork in the dataset would strictly be used in a straightforward, instrumental fashion, and there would be no reason for them to not use any other picture of a flower. An AI using my random artistic renderings would very likely be a violation of fair use, but because of the way AI generate their images, it may be very hard to prove that my image was used unless the AI hiccupped and left my watermark in the generated image -- thus the intellectual property laundering potential of these programs.

The legal issues in using an AI art generator to make commercial art would have to be argued in court. Is an image created by an AI art generator transformative or derivative? This would likely have to be argued on a case by case basis. The real meat here would be, would the individual responsible for compiling the data set for the AI also be responsible for getting permissions from artists when their art is added to the generator, because the art generated may not be sufficiently transformative? Must Disney allow Mickey Mouse to be used in the generator because of the likelihood of the generated work being parody, or can it disallow Mickey's addition to these data sets outright? What are the implications of this for other artists? Etc.

Honestly I think the misunderstanding of the actual problems with these AI art generators is not because people don't understand how AI works (even though they don't), but because they don't understand how copyright and intellectual property work. While the DMCA has changed this slightly, it's still very rare for randos on the internet to get smacked for misusing or stealing art they find online while the legal system has been coping with integrating new technology doing copyright infringement since copyright has existed. The people freaking out definitely seem like they have never had to deal with purchasing a stock image or getting permission for music sampling.

The idea that there's no humans involved with creating AI art beyond the user typing input is just demonstrably false. If I type in Frank Miller into a generator and it creates something Frank Miller-esque, then Frank Miller was involved with the creation of it. If these generators have not already paid the artists for the data they've trained their AI on, then it's extremely likely we have another Napster on our hands. I don't think comparing AI generated art to music streaming is actually a bad comparison -- it could be very bad for artists in the end, but in a totally different way than the initial doomsayers claimed. It's easy to imagine people who were already stealing art putting the art through an AI to tweak it to make it more difficult for artists to find and send them a DMCA takedown. It's easy to imagine AI generated art replacing stock images in many cases, and the artists that produce stock getting a smaller and smaller cut because, while their images are being used, they're only being used "in part" so the companies facilitating this decide they deserve less money for it. I can even imagine a far future where the final product of art is so untouched by human hands because all human-made art goes into the art-slush and what is wanted by the consumer is pulled out as needed, but the original human-made art was still necessary. It's hard for me to imagine AI generated art replacing huge swaths of the art market with "free" art where it wasn't before, because the US government has prevented that from happening repeatedly -- from photocopiers, to VCRs, to Napster, ad nauseum. The toes being stepped on by these generators are too big to ignore.

I keep reading doomsday declarations about what AI art will do to actual artists and their possibility of getting paid and at this point I’m convinced that everyone writing about this is missing the point. Artists have not been paid what they’re worth for a long time, either by exploitation or outright theft of their work. The homogenized, regurgitated slopification of art — no, I’m sorry, content — has been going on forever in the form of Save The Cat making all Hollywood movies the same, the MCU taking over cinema, the Penguin Random House/Simon and Schuster merger (including a hearing where they admitted they have no idea how books get popular), the insane scheduling requirements on Instagram to get any attention whatsoever, “crunch time” ruining game creators lives, all the way down to T-shirt bots trawling Twitter. If you read Little Women, Jo gets paid about the same amount in dollars for her short story during the Civil freaking War as a writer today would get upon winning a similar contest. I’m not saying it can’t get worse, but the idea that AI will change the fact that companies and unscrupulous individuals will do anything to avoid paying artists for their work, up to and including outright theft, by convincing them and everyone else that all “art” is essentially interchangeable, is nothing new, to the point that I wonder where the fuck anyone making these statements about AI art has been for the last ten years at least.

I keep reading doomsday declarations about what AI art will do to actual artists and their possibility of getting paid and at this point I’m convinced that everyone writing about this is missing the point. Artists have not been paid what they’re worth for a long time, either by exploitation or outright theft of their work. The homogenized, regurgitated slopification of art — no, I’m sorry, content — has been going on forever in the form of Save The Cat making all Hollywood movies the same, the MCU taking over cinema, the Penguin Random House/Simon and Schuster merger (including a hearing where they admitted they have no idea how books get popular), the insane scheduling requirements on Instagram to get any attention whatsoever, “crunch time” ruining game creators lives, all the way down to T-shirt bots trawling Twitter. If you read Little Women, Jo gets paid about the same amount in dollars for her short story during the Civil freaking War as a writer today would get upon winning a similar contest. I’m not saying it can’t get worse, but the idea that AI will change the fact that companies and unscrupulous individuals will do anything to avoid paying artists for their work, up to and including outright theft, by convincing them and everyone else that all “art” is essentially interchangeable, is nothing new, to the point that I wonder where the fuck anyone making these statements about AI art has been for the last ten years at least. But Disney is Disney. What about everyone else? I am not a lawyer, but I think this gets both easier and harder. As long as we're discussing fair use of images, Mickey Mouse at a strip club could be argued to be a parody or criticism somehow, while, say, if a drawing I made of a flower I found in my backyard was added to the data set, it would be really hard to argue anything made with it would be parody or criticism of the original work because I'm a nobody. There would be nothing specific in that image to parody or criticize because I am not known enough to parody or criticize. The use of my artwork in the dataset would strictly be used in a straightforward, instrumental fashion, and there would be no reason for them to not use any other picture of a flower. An AI using my random artistic renderings would very likely be a violation of fair use, but because of the way AI generate their images, it may be very hard to prove that my image was used unless the AI hiccupped and left my watermark in the generated image -- thus the intellectual property laundering potential of these programs.

But Disney is Disney. What about everyone else? I am not a lawyer, but I think this gets both easier and harder. As long as we're discussing fair use of images, Mickey Mouse at a strip club could be argued to be a parody or criticism somehow, while, say, if a drawing I made of a flower I found in my backyard was added to the data set, it would be really hard to argue anything made with it would be parody or criticism of the original work because I'm a nobody. There would be nothing specific in that image to parody or criticize because I am not known enough to parody or criticize. The use of my artwork in the dataset would strictly be used in a straightforward, instrumental fashion, and there would be no reason for them to not use any other picture of a flower. An AI using my random artistic renderings would very likely be a violation of fair use, but because of the way AI generate their images, it may be very hard to prove that my image was used unless the AI hiccupped and left my watermark in the generated image -- thus the intellectual property laundering potential of these programs.